Các vấn đề thực tế khiến việc ước tính nợ trực tiếp từ trái phiếu của công ty trở nên vô cùng khó khăn, nếu không muốn nói là không thể. Cụ thể, các công ty có thể phát hành nhiều trái phiếu và sự không đồng nhất của các trái phiếu đó có thể khiến việc xác định trái phiếu đại diện trở nên khó khăn. Ngoài ra, ngay cả khi một trái phiếu như vậy có thể được xác định, thị trường trái phiếu rất kém thanh khoản và việc tìm kiếm một khoảng giá đáng tin cậy cho một trái phiếu như vậy có thể là một thách thức. Thay vào đó, Tòa án tại DFC Opinion đề nghị sử dụng các beta nợ vay theo xếp hạng tín dụng được báo cáo trong Chi phí vốn của Pratt và Grabowski.

Trong cuốn sách đó, các tác giả ước tính các beta nợ bằng cách sử dụng "đường SML (Đường thị trường chứng khoán) với chi phí nợ vay đã điều chỉnh thuế" của Benninga-Sarig như sau:

trong đó RD là chi phí nợ vay, RF là lãi suất phi rủi ro βD là beta nợ vay, RM là tỷ suất lợi nhuận của thị trường và t là thuế suất doanh nghiệp. Công thức Benninga-Sarig được phát triển để đi đến cách tiếp cận giống như CAPM khi có các mức thuế khác nhau đối với nợ và vốn chủ sở hữu và phương pháp này, ngoài việc sửa đổi SML cho nợ vay, còn yêu cầu phương trình SML vốn chủ sở hữu được sửa đổi (tức là không còn sử dụng CAPM nữa) và điều chỉnh công thức beta không vay nợ (tức là bạn không thể sử dụng các công thức beta không vay nợ tiêu chuẩn, như được thảo luận dưới đây). [3] Do đó, các khoản nợ được báo cáo trong Chi phí vốn được tính theo cách không nhất quán với CAPM được sử dụng bởi những người hành nghề.

Hơn nữa, trong một ấn bản sau này của cuốn sách mô hình tài chính dựa trên Chi phí vốn, ngay cả tác giả cũng đặt câu hỏi về tính hữu ích của công thức mà ông đã phát triển. Cụ thể, Benninga viết:

"Mặc dù CAPM được điều chỉnh thuế phù hợp hơn với nền kinh tế có thuế, chúng tôi thú nhận rằng - với những điều không chắc chắn xung quanh chi phí tính toán vốn - sự khác biệt giữa CAPM cổ điển và CAPM được điều chỉnh thuế có thể không đáng để gặp rắc rối." [4]

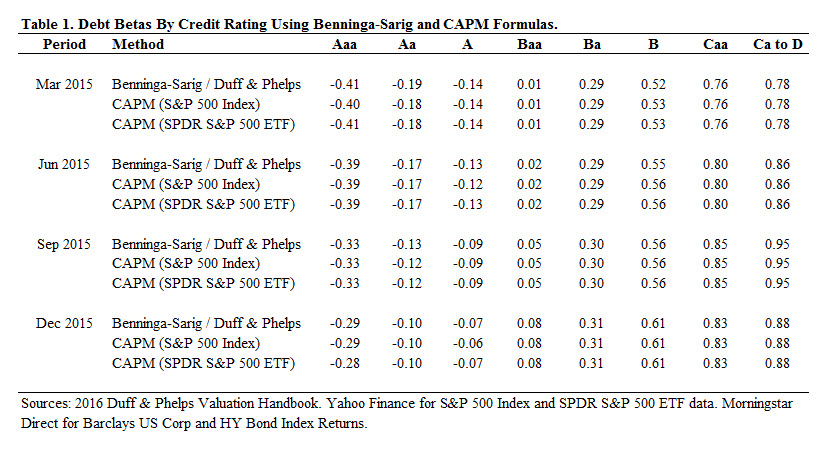

Do đó, chúng ta phải xác định xem có bất kỳ lợi ích nào khi sử dụng công thức Benninga-Sarig hay không. Như một thử nghiệm đơn giản, tôi so sánh các beta nợ vay được báo cáo trong Sổ tay định giá Duff &; Phelps 2016, sử dụng cùng một công thức Benninga-Sarig như Chi phí vốn, nhưng sử dụng dữ liệu cập nhật cho bốn quý của năm 2015 với các beta nợ vay được tính bằng CAPM. [5] Để tăng tính nghiêm ngặt, tôi sử dụng hai proxy thị trường cho mô hình thị trường của mình: Chỉ số S&P 500 và chỉ số SPDR S&P 500 ETF. Tôi lấy dữ liệu giá cho hai proxy thị trường từ Yahoo Finance. Theo phương pháp luận trong Sổ tay định giá Duff &; Phelps, tôi sử dụng Barclays US Corp và HY Bond Indexes từ Morningstar Direct cho dữ liệu chỉ số trái phiếu theo xếp hạng tín dụng và các beta nợ vay được ước tính bằng cách sử dụng lợi nhuận hàng tháng trong 05 năm. Kết quả xét nghiệm của tôi được báo cáo trong Bảng 1.

Như kết quả tại Bảng 1 cho thấy, hầu như không có sự khác biệt trong các beta được tính toán bằng cách sử dụng công thức Benninga-Sarig và CAPM. Do đó, dường như không có lợi ích thực tế nào khi sử dụng các beta nợ vay theo Benninga-Sarig thay vì CAPM để có thể bù đắp cần thiết do việc đi chệch khỏi CAPM và các công thức beta không vay nợ tiêu chuẩn. Hơn nữa, việc sử dụng CAPM mang lại lợi ích bổ sung là cho phép người hành nghề sử dụng một phương pháp nhất quán để tính toán cả beta vốn chủ sở hữu và nợ vay (tức là sử dụng cùng một khoảng thời gian và thời đoạn ước tính tỷ suất sinh lời).

Công thức beta không vay nợ theo Fernandez vs. Hamada

Tòa án tại DFC Opinion ủng hộ việc sử dụng Công thức Hamada để tính beta không vay nợ so với Công thức Fernandez vì họ cho rằng Công thức Hamada "được chấp nhận rộng rãi, dễ hiểu và không bị tranh cãi về việc liệu nó có được tính toán đúng hay không". [6] Quan sát này rất thú vị vì chỉ có một đầu vào phân biệt hai công thức. Để xem làm thế nào, lưu ý rằng công thức Fernandez là:

trong đó βL là beta có vay nợ, βU là beta không vay nợ, βD là beta nợ vay, t là thuế suất doanh nghiệp, D là giá trị nợ và E là giá trị vốn chủ sở hữu. [7] Nếu chúng ta giả định rằng βD = 0, thì phương trình (1) trở thành

đây chính là Công thức Hamada. Do đó, câu hỏi quan trọng khi lựa chọn giữa hai công thức này là mức độ hợp lý của giả định rằng beta nợ vay của công ty bằng 0.

Vì ít nhất ba lý do, tôi cho rằng rất khó có khả năng nợ vay của một công ty sẽ có beta bằng 0, điều này ủng hộ việc sử dụng công thức phi đòn bẩy với beta nợ vay không bằng 0 như Công thức Fernandez. Đầu tiên, theo CAPM, một tài sản zero-beta dự kiến sẽ mang lại tỷ suất sinh lời phi rủi ro, nhưng các nhà đầu tư có thể sẽ không xem xét đầu tư vào nhiều hoặc bất kỳ khoản nợ doanh nghiệp nào nếu khoản nợ chỉ được kỳ vọng mang lại lãi suất phi rủi ro. Thứ hai, các nghiên cứu trước đây báo cáo beta nợ vay cho các danh mục xếp hạng rộng không bằng 0. Ví dụ, vào năm 1991, Cornell và Green đã xuất bản một bài báo báo cáo trái phiếu cao cấp có beta nợ vay là 0,25 và trái phiếu cấp thấp có beta nợ vay là 0,29 [8] và vào năm 2011, Groh và Gottschalg đã xuất bản một bài báo báo cáo trái phiếu cao cấp có beta là 0,296 và trái phiếu cấp thấp có beta là 0,410. [9] Thứ ba, như thể hiện trong Bảng 1, các beta nợ vay bất kể xếp hạng tín dụng không có khả năng bằng 0.

[2] Benninga, S. and O. Sarig. 2003. “Risk, Returns, and Values in the Presence of Differential Taxation.” Journal of Banking & Finance 27, pp. 1123–1138.

***

English Version:

Estimating Debt Betas and Beta Unlevering Formulas

Use of Benninga-Sarig to Estimate Debt Betas in a Valuation Engagement

In the July 8, 2016 In re Appraisal of DFC Global Corp. Opinion (DFC Opinion), the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware suggested that debt betas should be estimated for individual companies and it cited Pratt and Grabowski’s Cost of Capital as a source for debt betas based on the firm’s credit rating. In addition, the Court also adopted the Hamada Formula over the Fernandez Formula to unlever betas because it believed the Hamada Formula “is widely accepted, readily understood, and not subject to dispute about whether it is properly calculated.” In this article, Clifford Ang critiques these two approaches and argues these two approaches may not be the best practice for valuation practitioners.

In the July 8, 2016 In re Appraisal of DFC Global Corp. Opinion (DFC Opinion), the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware suggested that debt betas should be estimated for individual companies and it cited Pratt and Grabowski’s Cost of Capital as a source for debt betas based on the firm’s credit rating.[1] In addition, the Court also adopted the Hamada Formula over the Fernandez Formula to unlever betas because it believed the Hamada Formula “is widely accepted, readily understood, and not subject to dispute about whether it is properly calculated.”[2] As I explain below, using these two approaches may not be the best practice for valuation practitioners.

Estimating Debt Betas

Practical issues make estimating debt betas directly from the firm’s bonds extremely challenging, if not impossible. Specifically, firms may issue many bonds and the heterogeneity of those bonds may make identification of a representative bond difficult. In addition, even if such a bond could be identified, the bond markets are very illiquid and finding a reliable price series for such a bond could prove challenging. As an alternative, the Court in the DFC Opinion suggested using debt betas by credit rating reported in Pratt and Grabowski’s Cost of Capital.

In that book, the authors estimate debt betas using the Benninga-Sarig “tax adjusted cost of debt SML [Security Market Line],” which is ![]()

where RD is the cost of debt, RF is the risk-free rate, βD is the debt beta, RM is the return on the market, and t is the corporate tax rate. The Benninga-Sarig formula was developed to arrive at a CAPM-like approach when there are different tax rates for debt and equity and this methodology, in addition to modifying the SML for debt, also requires a modified equity SML equation (i.e., you are no longer using the CAPM) and a modified beta unlevering formula (i.e., you cannot use the standard beta unlevering formulas, such as those discussed below).[3] As a consequence, the debt betas reported in Cost of Capital are calculated in a manner that is inconsistent with the CAPM that is used by practitioners.

Moreover, in a later edition of the financial modeling book relied upon in the Cost of Capital, even the author questions the usefulness of the formula he developed. Specifically, Benninga writes:

“Although the tax-adjusted CAPM is more consistent with an economy with taxation, we confess that—given the uncertainties surrounding cost of capital computations—the difference between the classic CAPM and the tax-adjusted CAPM may not be worth the trouble.”[4]

Therefore, we have to determine whether there are any benefits to using the Benninga-Sarig formula. As a simple test, I compare the debt betas reported in the Duff & Phelps 2016 Valuation Handbook, which uses the same Benninga-Sarig formula as the Cost of Capital but using updated data for the four quarters of 2015 against debt betas calculated using the CAPM.[5] For robustness, I use two market proxies for my market model: S&P 500 Index and the SPDR S&P 500 ETF. I obtain price data for the two market proxies from Yahoo Finance. Following the methodology in the Duff & Phelps Valuation Handbook, I use the Barclays U.S. Corp and HY Bond Indexes from Morningstar Direct for the bond index data by credit rating and the debt betas are estimated using five years of monthly returns. The results of my test are reported in Table 1.

As Table 1 shows, there is virtually no difference in the calculated betas using the Benninga-Sarig formula and the CAPM. Therefore, there appears to be no practical benefit to using the Benninga-Sarig debt betas over the CAPM that would offset the need to deviate from the CAPM and standard beta unlevering formulas. Moreover, using the CAPM gives the added benefit of allowing the valuation practitioner to use a consistent methodology to calculate both the equity and debt betas (i.e., using the same return interval and estimation period).

Fernandez vs. Hamada Unlevering Beta Formulas

The Court in the DFC Opinion favored the use of the Hamada Formula to unlever debt betas over the Fernandez Formula because it opined that the Hamada Formula “is widely accepted, readily understood, and not subject to dispute about whether it is properly calculated.”[6] This observation is interesting because only one input differentiates the two formulas. To see how, note that the Fernandez formula is![]()

where βL is the levered beta, βU is the unlevered beta, βD is the debt beta, t is the corporate tax rate, D is the value of debt, and E is the value of equity.[7] If we assume that βD = 0, then Eq. (1) becomes

which is the Hamada Formula. Therefore, the important question when choosing between these two formulas boils down to how reasonable is an assumption that the firm’s debt beta is equal to zero.

For at least three reasons, I argue it is highly unlikely that a firm’s debt would have a beta of zero, which supports the use of an unlevering formula that incorporates a non-zero debt beta such as the Fernandez Formula. First, based on the CAPM, a zero-beta asset is expected to yield the risk-free rate of return, but investors will likely not consider investing in many, or any, corporate debt if the debt were only expected to yield the risk-free rate. Second, prior studies report debt betas for broad ratings categories that are not equal to zero. For example, in 1991, Cornell and Green published a paper that reported high-grade bonds have a debt beta of 0.25 and low-grade bonds have a debt beta of 0.29[8] and, in 2011, Groh and Gottschalg published a paper that reported high-grade bonds have a beta of 0.296 and low-grade bonds have a beta of 0.410.[9] Third, as shown in Table 1, debt betas regardless of credit ratings are unlikely to equal zero.

Summary

In the DFC Opinion, the Court implicitly suggested the use of two procedures: the Benninga-Sarig formula to estimate debt betas and the Hamada formula to unlever betas. As shown above, debt betas estimated using the Benninga-Sarig formula require the use of a different Security Market Line and beta unlevering formula, but the ultimate results are virtually identical to debt betas estimated using the CAPM. We also showed that the Hamada formula is the Fernandez formula when you assume a debt beta of zero, but the zero debt beta assumption required by the Hamada formula unlikely holds in practice. Therefore, using these two approaches may not be the best practice for valuation practitioners.

* Vice President at Compass Lexecon. E-mail: cang@compasslexecon.com. Opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and are not opinions of Compass Lexecon or its other employees.

[1] DFC Opinion note 144.

[2] DFC Opinion at 33.

[3] Benninga, S. and O. Sarig. 2003. “Risk, Returns, and Values in the Presence of Differential Taxation.” Journal of Banking & Finance 27, pp. 1123–1138.

[4] Benninga, S. 2014. Financial Modeling, 4th ed. MIT Press, p. 98.

[5] Consistent with what is typically done in practice, I estimate betas using a market model of the form: RD = a + b * RM.

[6] DFC Opinion at 33.

[7] This formula appeared in a published article in 2004 by Fernandez [“The Value of Tax Shields Is Not Equal to the Present Value of Tax Shields,” Journal of Financial Economics 73, p. 145–165]. However, the form of the Fernandez Formula has been derived from beta factors based on the CAPM in a published article in 1982 by Yagill [“On Valuation, Beta, and the Cost of Equity Capital: A Note,” The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 17, pp. 441–449].

[8] Cornell, B. and K. Green. 1991. “The Investment Performance of Low-Grade Bond Funds.” The Journal of Finance 46, pp. 29–48, at p. 34.

[9] Groh, A. and O. Gottschalg. 2011. “The Effect of Leverage On the Cost of Capital of U.S. Buyouts.” Journal of Banking & Finance 35, pp. 2099–2110, at p. 2019.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét